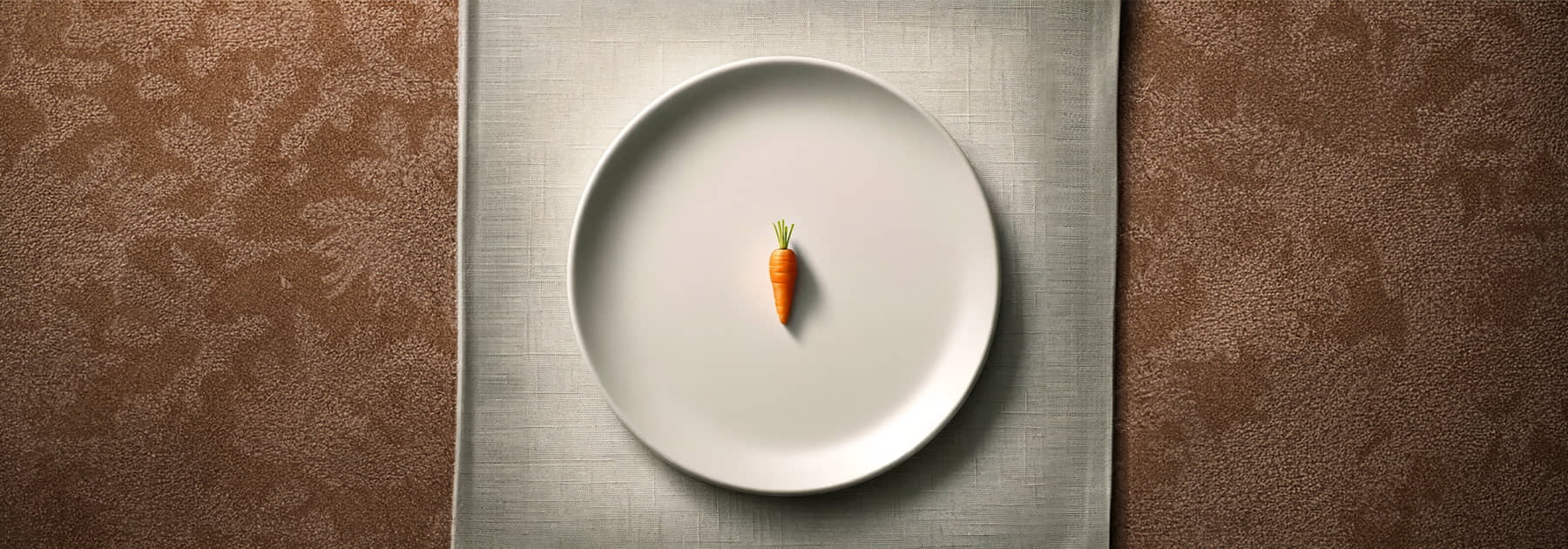

Most tourists have their own pet story about going to a US restaurant for the first time and being shocked at the size of the portions. I remember being floored at a restaurant in San Francisco when, after ordering the house specialty, I was served an entire roast chicken. Less than two minutes later came the sides – enough potatoes to sink a battleship, together with a head of broccoli the size of a small child.

There doesn’t seem to be much correlation between the size of the portion one gets in a restaurant with the price of the meal. In fact, they’re often inversely proportional. Most American chain restaurants offer a portion size that no normal person could ever hope to finish.

I’ve been told this is deliberate, and meant to ensure that you have leftovers to take home with you. Of course, critics say such disregard of portion control is a contributory factor in the growing obesity epidemic in the USA, as well as many other countries around the world.

Offering More Just For The Sake Of It

The result is most food service businesses feel expected to offer over-the-top portions in order to compete. Customers have come to equate “more” with “better”. Unless your business is playing the same game as the place across the street, you’re going to lose.

The problem with such thinking is it’s lazy. Once you start playing by the competition’s rules, you’ve already lost. Just because you’re trying to solve the same problem doesn’t mean you have to offer the same solution.

Finding anything normal-size is becoming increasingly difficult – and I don’t just mean regarding food portions. Do you really need that unlimited data plan for your phone, when you rarely even hit 1GB in an average month? How many of the hundreds of cable TV channels you pay for, do you actually watch?

In a culture where excess is expected, businesses of all sizes seem to be constantly under pressure to offer more for the same or – even worse – for less. One problem with such thinking is the cost of goods or services is a real cost that doesn’t scale downward. Overheads such as rent, utilities, and salaries stay pretty much the same. As a business strategy, such thinking puts you on your way to being perceived as a commodity.

So how does your business get around this without leaving customers feeling short-changed, or that you’re offering less value than the competition?

It’s Not About The Price. It’s About The Value Proposition.

One trend in your favor is that there are plenty of people happy to pay the same amount (if not more) for a normal-size option. It’s not necessarily about wanting “more,” or “bigger.” It’s often about “value.” If your customers can see where their hard-earned money is going within the transaction, and can attribute value to the commercial exchange, then you’re winning. Offering less can be presented in ways that are considered to offer similar – or greater – value.

Teeny-size packs of snacks shouting about how they’re “100-calorie servings.” Ten styles of jeans instead of twenty. As a business strategy, smaller can sometimes be the new big.

What does ‘value’ look like? That depends on your customers. It could be the 11 secret herbs and spices, or your awesome homemade hot sauce. It could be your glowing reviews on Yelp or TripAdvisor, or recommendations on LinkedIn. Maybe it’s your free next-day delivery, extended weekend opening hours, no-question returns policy, or amazing customer service. Different audiences have different criteria of what value means to them. It’s your job to tap into those influences and deliver on their expectations.

The 80/20 Rule – aka Pareto Principle – Explained In Hamburgers

The McDonald’s fast food chain was started in 1940 by brothers Richard and Maurice McDonald. At the time, the restaurant had a large and varied menu. As well as hamburgers the restaurant sold hotdogs, barbecue beef and pork, fried chicken, even chilli.

The problem with having such a varied menu was that many items had to be cooked to order. Only when the customer has given their order could the cooking begin. That took time – and reduced the number of orders the restaurant could fulfil in a particular timeframe.

After a couple of years the McDonald brothers took a step back and re-evaluated their business. They discovered that over 80% of revenue from the restaurant came from just three things: hamburgers, fries, and drinks.

So they made a bold decision. They removed everything else from the menu and concentrated on making the best hamburgers/fries/drinks they could – delivering the order faster than anyone else. Since the menu was now so small, they could bet on pre-cooking each menu item. The result was customers orders were fulfilled immediately.

What the McDonald brothers did was based on The Pareto Principle, also known as the 80/20 Rule. You can summarize it as saying 80% of the return on an action comes from 20% of effort. In terms of business it’s that 80% of your sales are from 20% of your customers. Or that 80% of support calls come from 20% of customers.

What Richard and Maurice did was focus their business on serving the 80% of their customers better than anyone else, even if it meant serving 20% of their customers less well. Today McDonald’s is a $21Bn business with more than 37,000 locations and 200,000 employees spread across 119 countries.

The 80/20 Rule: A “Less Is More” Marketing Strategy

The McDonald’s story is more than simply an example of “less is more”. It’s about identifying what your customer sees as having value to them – and delivering on that in spades. It’s not about seemingly offering less than the competition. It’s about reframing the buying decision around considerations the customer sees as being of value to them.

Adding more features to a product is not the same thing as providing more value. But neither is serving me an entire – though mediocre – roast chicken, when a couple of awesome-tasting drumsticks would’ve made me happier.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Gee Ranasinha is CEO and founder of KEXINO. He's been a marketer since the days of 56K modems and AOL CDs, and lectures on marketing and behavioral economics at two European business schools. An international speaker at various conferences and events, Gee was noted as one of the top 100 global business influencers by sage.com (those wonderful people who make financial software).

Originally from London, today Gee lives in a world of his own in Strasbourg, France, tolerated by his wife and teenage son.

Find out more about Gee at kexino.com/gee-ranasinha. Follow him on on LinkedIn at linkedin.com/in/ranasinha or Instagram at instagram.com/wearekexino.

Recent articles:

How Behavioral Science Thinking Improves Marketing Effectiveness

Dark Social: The Hidden Conversations Marketers Can’t See

Marketing In A Recession: How To Weather The Storm

How To Convince A Marketing Skeptic

Privacy Protection: Why Ad Tracking Must End

Marketing Isn’t About Being Brave: It’s About Being Effective